Last week, the FDA sent a sternly-worded letter to the personal genomics company 23andMe, arguing that the company is marketing an unapproved diagnostic device. Many have weighed in on this, but I’d like to highlight a thoughtful post by Mike Eisen.

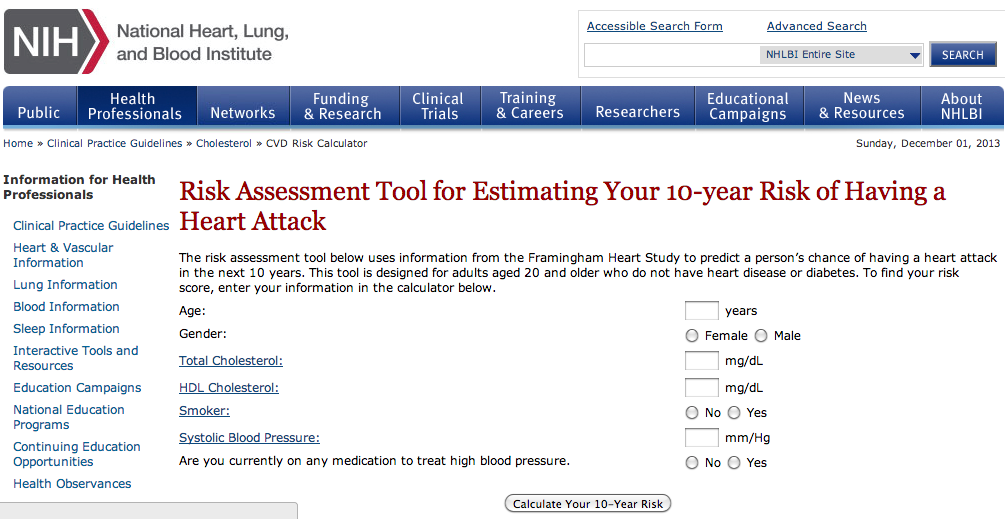

Eisen makes the important point that interpreting the genetics literature is complicated, and a company (like 23andMe) that provides this interpretation as a service could potentially add value. I’d like to add a simple point: this is absolutely not limited to genetics. In fact, there are already many software applications that calculate your risk for various diseases based on standard (i.e. non-genetic) epidemiology. For example, here’s a (NIH-based) site for calculating your risk of having a heart attack:

And here’s a site for calculating your risk of having a stroke in the next 10 years:

And here’s one for diabetes. And colorectal cancer. And breast cancer. And melanoma. And Parkinson’s.

I don’t point this out because it leads to an obvious conclusion; it doesn’t. But all of the scientific points made about risk prediction from 23andMe (the models are not very predictive, they’re missing a lot of important variables, there are likely errors in measurements, etc.) of course apply to traditional epidemiology as well. Ultimately, I think a lot rides on the question: what is the aspect of 23andMe that sets them apart from these websites and makes them more suspect? Is it because they focus on genetic risk factors rather than “traditional” risk factors (though note several of these sites ask about family history, which of course implicitly includes genetic information)? Is it the fact that they’re a for-profit company selling a product? Is it something about the way risks are reported, or the fact that risks for many diseases are presented on a single site? Is it because some genetic risk factors (like BRCA1) have strong effects, while standard epidemiological risk factors are usually of small effect? Or is it something else?

RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter

It’s a good point, it’s also worth saying that different sites with different algorithms for the same disease give different results (like the different PG companies). Further, some sites, like WebMD, are for profit and are “doing medicine” but without regulation

However 23andMe have been selling since 2007 and the wording of the FDA letter seems implies that the current action is due to a shift from class II to class III because of the serious genetic issues more or less “diagnosed” introduced recently into the service. Class II does nto require pre-market review while Class III does. This is what appears to set them apart and it seems a reasonable approach. The FDA are not saying that this stuff cannot be sold DTC, but are saying that it needs to be reviewed before being sold. We know 23andMe and we know Illumina – they are serious and we can have confidence in their quality. But what about other companies, that are already jumping in with BRCA and other tests, do we know them, are they trustworthy, should there be a mechanism for demonstrating that they are trustworthy?

If 23andme had not dropped the ball or whatever, they may well be selling a reviewed FDA approved Class III device DTC for $99 by now. I think that would have been a much better investment than TV ads!

Thanks Keith. So that’s one vote for the main difference between 23andMe and other online risk calculators being the presence of high-penetrance alleles like BRCA. I think I agree with that; certifying accuracy at these sites seems like a good idea.

Sorry, Keith, I’m still not sure I buy the argument for why 23andme is fundamentally any different than web sites. If 23andme is guilty of false or deceptive advertising, then that’s a job for the FTC, not the FDA.

Everything about FDA regulation of online advice seems based on the idea that somehow people are too stupid to be trusted with information about themselves.

The limit of your question is should fortune tellers be regulated? I think they should be, and they are. So if one interpolates then I think yes, interpretation of traditional epidemiology should also be regulated. Whether the FDA should regulate or some other agency/legal mechanism seems to me to be a secondary issue albeit an important one that is probably timely to debate.

Thanks Lior. I was wondering if someone would take that position. My guess was no :)

A central issue is the probability that a particular genetic predisposition is likely to occur, and following on that, the actionability in response to the presented risk.

Prevention, for the examples you mention, breast cancer, melanoma, diabetes and even Parkinson’s, is to some degree actionable.

One the other hand, 23andme, by the nature of the volume of the data they present, will potentially saddle users with a high degree of risk for a number of diseases for which no action can be taken.

Alzheimer’s comes to mind.

The situation is summed up succinctly by the comments of a neurologist I heard quoted recently: “23andme creates chaos and walks away.”

In the end, you are the person most responsible for your health and you have the final say for any medical decision (at least while conscious). If someone wants to use these tools, or read primary literature on disease risk, or talk to their relatives, then I think it is their right and that it is overall a good thing.

These other NIH-based sites are useful tools to gauge general risk, just as the information contained in 23andme’s disease profile are useful tools for general risk, and I think both are good for increasing awareness. Let’s put aside the accuracy issue, since that has not been resolved to the FDA’s liking, and I think we can presume that with a bit more cost the test could be as accurate as any clinical test.

I don’t think the volume of information is the issue, unless you don’t want to consider all the ways you might die (I promise there are more). If you don’t want to know, then you don’t have to take the test. But, if you want to know your risks, then I think you should be able to find out. Also, I am anxious about “regulation” – would this apply to reading a paper with a linear model for breast cancer risk and then making a web site with a CGI script to show numbers to people? Or, would we say that people should not be able to do PCR on themselves?

These sites all have some kind of a disclaimer, like the NCI breast cancer site http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/), they say this:

“The Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool was designed for use by health professionals. If you are not a health professional, you are encouraged to discuss these results and your personal risk of breast cancer with your doctor.”

In all cases, these information should be discussed with your doctor, and no doctor would act on these web sites’ data alone. So, in the end, I think these sites are useful for people who want to be empowered and active in their health, and surely not for hypochondriacs (who will, by definition, worry anyway). Getting people more information, assuming it is accurate, I think is a good thing. Teaching them how to act on it is a blend of a scientific, cultural, sociological, and pedagogical problem, but they need to get information in the first place so they can be active and vigilant in their health, which is ultimately in their own hands.

We know hardly anything about our genomes, so how can anything 23andMe claim be taken with anything but a pinch of salt.

Better to spend the money researching your family’s medical history, like constructing a medical-oriented family tree. If you have a genetic disorder that’s life threatening it’s more likely to be apparent.

One of the challenges with this discussion is that folks are considering 23andMe to be “a test” when in fact it is a collection of multiple “tests”, some of which are GWAS-based risk estimates from one or more SNPs, and some of which are reporting out on established variants that have known clinical significance.

I’ve done several 23andMe consults (I’m a genetic counselor) and have used the service myself. My take-home message for patients is that the GWAS-based risk estimates (the “health risks” tab) are interesting, but generally wouldn’t be enough to change clinical care. In fact, some times those risk estimates can and do cause a false reassurance– the message boards are rife with folks who are delighted to find that their colon cancer risk is lower than average, despite having three family members with the disease…. yes, there are disclaimers, and yes, caveat emptor, but there are many examples of over-interpreting the GWAS-based information.

The carrier tests and pharmacogenomic tests are similar (if not the same) as the tests that would be ordered by a health care provider; I encourage patients to focus on these as “actionable” and to repeat in a clinical lab that will confirm and provide a report. I do like the autonomy and privacy that DTC affords patients/consumers, but if medical care or a prescription might be changed, confirmation is critical. One aspect of this is the chance of sample mix-up (possible in any lab), but at least with a provider-ordered test there is a chain of custody where the chance of getting the wrong result is minimized… when I order a saliva-based clinical test, I have to witness the patient providing the sample. The other issue is that it’s just sound medical practice to have a test report documented in the medical record so everyone is working off of the same information from a trusted source.

At the end of the day, anything that gets people excited about genetics is a good thing. But if you want to get a sense of how many users are overinterpreting their results, look no further than the message boards where folks are reporting their custom supplement use after being “diagnosed with MTHFR disease”, or who were angry that their doctor refused to order an EGD because of their increased risk of esophageal cancer (that went from 0.05% to 0.07%).

Part of our job as genetic counselors is to describe the limitations of genetic tests (and, increasingly, risk models that incorporate family history or SNP data) so patients can make informed choices about their health. Overall, I’d like to see more people engage with their genomic data, but to also seek the advice of providers trained in clinical genetics to help sort out the useful from the less useful.

There’s a difference between the expert user and the novice user of the data sets. If you’re going to report medical information you must take into account the minimal background knowledge of the novice. That’s my personal opinion.

Excellent point. In order to perhaps strengthen your argument, I would add that health insurance companies, including BCBS, have similar online “health risk assessment” screening tests. These screening tests are only available to subscribers, thus, they are part of the healthcare services that BCBS is selling. (Note: even if premiums are paid indirectly via an employer, it is the subscriber who is paying as this is deemed to be part of the employee’s compensation package).

Not only does BCBS provide a “Health Risk Assessment” report for many of the exact same things as the 23andMe reports, but it goes farther than 23andme by providing specific advice on how this risk assessment relates to “your healthy practices” and advises specifically “where improvement can be made” with “recommended programs to help reduce [the subscriber’s] risks” based upon the results of the “health risk assessment” results.

So, how is BCBS’s “Health Risk Assessment” tool not a medical device if 23andme’s personal data is? Consumers pay for both of them. If anything, BCBS is potentially stepping over another FDA line by interpreting medical info and PROVIDING MEDICAL ADVICE WHILE PRESENTING ITSELF AS AN AUTHORITY ON SUCH MEDICAL MATTERS. That is usually a big legal no-no. So, when will the FDA be sending a cease and desist letter to BCBS?

Link to website to view intro page of tool: https://www.excellusbcbs.com/wps/portal/xl/mbr/fyh/healthyliving/hra/

I should have clarified above that the BCBS tool is different than the UCLA medical center tool because UCLA’s tool is available to anyone, whereas the BCBS tool is only available to paying subscribers. It’s not just that payment is involved (critical because that brings in the interstate commerce clause) but also that the requirement to provide your membership number means that the risk assessment and specific health recommendations are not for general public use. Thus, whereas UCLA might claim that its information is only a tool for sharing general health knowledge to the general public, BCBS cannot say that. Their “health assessment” is clearly for a specific member based upon that member’s personal health information. Therefore, it should not be viewed as any different than 23andme’s health information reports.

Sorry for multiple posts, but wanted to add that the Cigna Health Risk Assessment tool for its subscribers is even more specific in how it evaluates specific, personal health risks for specific diseases, including based upon family history data. Cigna is doing the same thing as 23andme in this aspect, except 23andme’s data is possibly more reliable. Per Cigna its tool will:

■ Identify and monitor your

personal health status;

■ Obtain a personalized analysis of

many preventable and

common conditions;

■ Review details of your

contributing risk factors; and

■ Access recommended steps for

improvement, interactive tools

and wellness information.

The assessment will cover areas

including:

■ Your current health conditions

■ Family health history and

lifestyle factors

Lee,

Thanks, I wasn’t aware of those sites.

Consider petitioning the White House (http://wh.gov/lKu2R) to overrule FDA’s 23andMe halt (http://bit.ly/Ix7JRP)

I encourage genetic counseling and confirmation of bad results, if one gets a bad result on DTC genetic testing. Let’s face it, no test is infallible, and when humans process it, especially hundreds or thousands of samples, it is even more prone to mistakes. I know what the testing involves, since I have an MS in a biologic science and an MD. “CLIA or no CLiA”, It is good to “trust but confirm”, in my opinion. in addition, more genetic biomarkers of disease are appearing, and can change the risk for some people who think they are free of risk based on out-dated test results. On the other hand, new research may show that there is less risk for a bad result than was once thought.

Therefore, I do not recommend that people engage in mass-market direct to consumer genetic health testing until we have more information about actual risks. That is because many people will not have access to genetic counsellors due to financial restraints. There will be unnecessary angst, and some people fall prey to charlatans who harp their expensive supplements to ward off the dreaded disease. Also, do we really know how accurate these mass-processed tests are?

Family history is still important. If uncle Charlie had colon cancer at age 44, I think one would get an early colonoscopy anyway, DTC testing or not.

I have a patient who has breast cancer at age 46. She has a strong family history of breast cancer. Her oncologist ordered the BRCA testing, paid for by her insurance (it is about 500$), and she was negative for the BRCA 1 and 2 gene. Go figure.

By the way, I am not the same “Lee” who posted prior to my one post. ;-)