Last week, the FDA sent a sternly-worded letter to the personal genomics company 23andMe, arguing that the company is marketing an unapproved diagnostic device. Many have weighed in on this, but I’d like to highlight a thoughtful post by Mike Eisen.

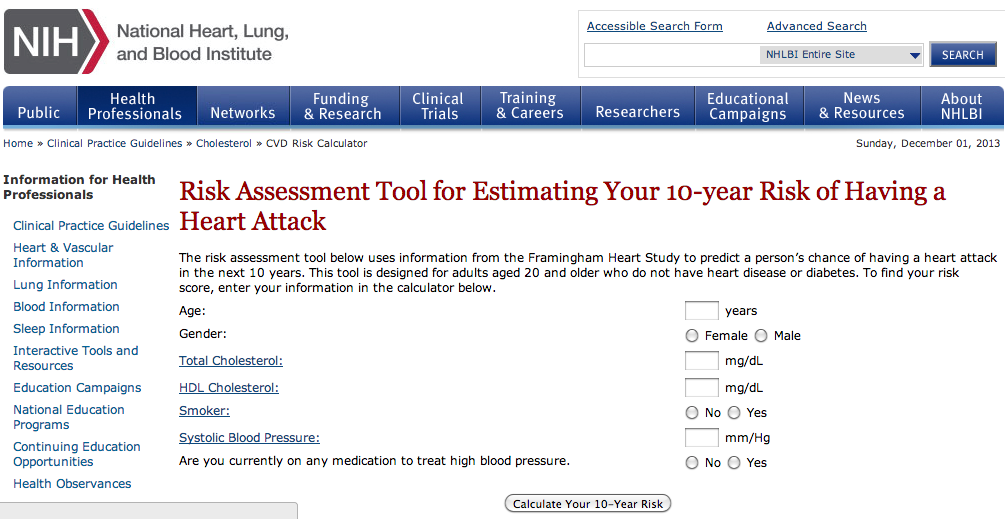

Eisen makes the important point that interpreting the genetics literature is complicated, and a company (like 23andMe) that provides this interpretation as a service could potentially add value. I’d like to add a simple point: this is absolutely not limited to genetics. In fact, there are already many software applications that calculate your risk for various diseases based on standard (i.e. non-genetic) epidemiology. For example, here’s a (NIH-based) site for calculating your risk of having a heart attack:

And here’s a site for calculating your risk of having a stroke in the next 10 years:

And here’s one for diabetes. And colorectal cancer. And breast cancer. And melanoma. And Parkinson’s.

I don’t point this out because it leads to an obvious conclusion; it doesn’t. But all of the scientific points made about risk prediction from 23andMe (the models are not very predictive, they’re missing a lot of important variables, there are likely errors in measurements, etc.) of course apply to traditional epidemiology as well. Ultimately, I think a lot rides on the question: what is the aspect of 23andMe that sets them apart from these websites and makes them more suspect? Is it because they focus on genetic risk factors rather than “traditional” risk factors (though note several of these sites ask about family history, which of course implicitly includes genetic information)? Is it the fact that they’re a for-profit company selling a product? Is it something about the way risks are reported, or the fact that risks for many diseases are presented on a single site? Is it because some genetic risk factors (like BRCA1) have strong effects, while standard epidemiological risk factors are usually of small effect? Or is it something else?

By now, we’re probably all familiar with Niels Bohr’s famous quote that “prediction is very difficult, especially about the future”. Although Bohr’s experience was largely in quantum physics, the same problem is true in human genetics. Despite a plethora of genetic variants associated with disease – with frequencies ranging from ultra-rare to commonplace, and effects ranging from protective to catastrophic – variants where we can accurately predict the severity, onset and clinical implications are still few and far between. Phenotypic heterogeneity is the norm even for many rare Mendelian variants, and despite the heritable nature of many common diseases, genomic prediction is rarely good enough to be clinically useful.

By now, we’re probably all familiar with Niels Bohr’s famous quote that “prediction is very difficult, especially about the future”. Although Bohr’s experience was largely in quantum physics, the same problem is true in human genetics. Despite a plethora of genetic variants associated with disease – with frequencies ranging from ultra-rare to commonplace, and effects ranging from protective to catastrophic – variants where we can accurately predict the severity, onset and clinical implications are still few and far between. Phenotypic heterogeneity is the norm even for many rare Mendelian variants, and despite the heritable nature of many common diseases, genomic prediction is rarely good enough to be clinically useful.

RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter

Recent Comments