Barbara Prainsack is at the Department of Social Science, Health & Medicine at King’s College London. Her work focuses on the social, regulatory and ethical aspects of genetic science and medicine.

Barbara Prainsack is at the Department of Social Science, Health & Medicine at King’s College London. Her work focuses on the social, regulatory and ethical aspects of genetic science and medicine.

More than seven years ago, my colleague Gil Siegal and I wrote a paper about pre-marital genetic compatibility testing in strictly orthodox Jewish communities. We argued that by not disclosing genetic results at the level of individuals but exclusively in terms of the genetic compatibility of the couple, this practice gave rise to a notion of “genetic couplehood”, conceptualizing genetic risk as a matter of genetic jointness. We also argued that this particular method of genetic testing worked well for strictly orthodox communities but that “genetic couplehood” was unlikely to go mainstream.

Then, last month, a US patent awarded to 23andMe – which triggered heated debates in public and academic media (see here, here, here, here and here, for instance) – seemed to prove this wrong. The most controversially discussed part of the patent was a claim to a method for gamete donor selection that could enable clients of fertility clinics a say in what traits their future offspring was likely to have. The fact that these “traits” include genetic predispositions to diseases, but also to personality or physical and aesthetic characteristics, unleashed fears that a Gattaca-style eugenicist future is in the making. Critics have also suggested that the consideration of the moral content of the innovation could or should have stopped the US Patent and Trademark Office from awarding the patent.

Continue reading ‘Guest post: 23andMe’s “designer baby” patent: When corporate governance and open science collide’

This is a guest post by Peter Cheng and Eliana Hechter from the University of California, Berkeley.

This is a guest post by Peter Cheng and Eliana Hechter from the University of California, Berkeley.

I have no strong family history of any disease, despite having 7 blood aunts and uncles and countless cousins. So when I sent my spit off to 23andMe at the start of the Genomes Unzipped project, I was expecting something very similar to

I have no strong family history of any disease, despite having 7 blood aunts and uncles and countless cousins. So when I sent my spit off to 23andMe at the start of the Genomes Unzipped project, I was expecting something very similar to

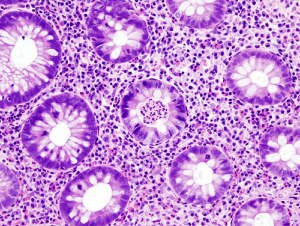

A paper in Nature Genetics this week reports the results of a large meta-analysis of GWAS studies into ulcerative colitis, which more than doubles the number of loci known for the disease from 18 to 47. This pushes the proportion of heritability explained from 11 to 16%, and sheds more light on the shared and non-shared pathways between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, along with the interplay with other immune and inflammatory disorders.

A paper in Nature Genetics this week reports the results of a large meta-analysis of GWAS studies into ulcerative colitis, which more than doubles the number of loci known for the disease from 18 to 47. This pushes the proportion of heritability explained from 11 to 16%, and sheds more light on the shared and non-shared pathways between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, along with the interplay with other immune and inflammatory disorders.

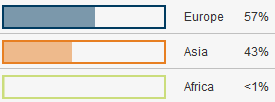

But last spring Daniel alerted me to the 23andMe “DNA Day” sale. It was affordable, and at that point enough of the readers of my weblog had been typed that I kept getting questions as to my own background (e.g., my family has the title Khan, so there was a question as to whether I carried the “Genghis Khan haplotype”). So I bit. At the time I recall emailing Dan and being excited that I’d be told I likely had brown eyes and was 75% “European” and 25% “Asian.” When my results came back, I was in for a mild surprise. The proportion to the left are calculated by 23andMe’s “ancestry painting” algorithm. As you can see, I’m more than 25% “Asian.” My initial reaction was that this seemed a touch high, but no worries, I would ask around and see which other South Asians had such a high value. After dozens of instances of “gene sharing,” the answer came back: none.

But last spring Daniel alerted me to the 23andMe “DNA Day” sale. It was affordable, and at that point enough of the readers of my weblog had been typed that I kept getting questions as to my own background (e.g., my family has the title Khan, so there was a question as to whether I carried the “Genghis Khan haplotype”). So I bit. At the time I recall emailing Dan and being excited that I’d be told I likely had brown eyes and was 75% “European” and 25% “Asian.” When my results came back, I was in for a mild surprise. The proportion to the left are calculated by 23andMe’s “ancestry painting” algorithm. As you can see, I’m more than 25% “Asian.” My initial reaction was that this seemed a touch high, but no worries, I would ask around and see which other South Asians had such a high value. After dozens of instances of “gene sharing,” the answer came back: none. RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter

Recent Comments