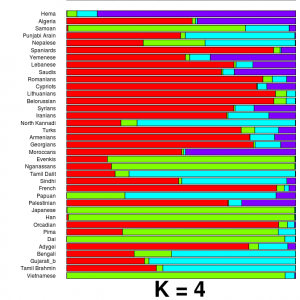

Razib Khan, more known for his detailed low-downs of population biology and history, has written an important post on Gene Expression, explaining in careful detail exactly how to run some simple population genetic analysis on public genomes, as well as on your own personal genomics data. The outcome of the tutorial is an ADMIXTURE plot (like the one to the left), showing what proportion of your genome comes from different ancestral populations. This sort of analysis is not difficult, but it can often be hard to know how to start, so Razib’s post gives a good landing point for people who want to dig deaper into their own genomes.

Razib Khan, more known for his detailed low-downs of population biology and history, has written an important post on Gene Expression, explaining in careful detail exactly how to run some simple population genetic analysis on public genomes, as well as on your own personal genomics data. The outcome of the tutorial is an ADMIXTURE plot (like the one to the left), showing what proportion of your genome comes from different ancestral populations. This sort of analysis is not difficult, but it can often be hard to know how to start, so Razib’s post gives a good landing point for people who want to dig deaper into their own genomes.

This tutorial also ties in to some political ideas that Razib has been talking about since the recent call to allow access to genomic information only via prescription. If you are worried about losing access to your genome, one option is to ensure that you do not require companies to generate and interpret your genome. As sequencing, genotyping and computing prices fall, DIY genetics becomes more and more plausible. Learn to discover things about your own genome, and no-one will be able to take that away from you. [LJ]

On the subject of regulation, the FDA’s meeting on DTC genetics (discussed by us last week) has sparked a mass of comment and criticism around the internet. Previous to our post Misha Angrist and our own Dan and Daniel reported on the meeting. Since then, the FDA released a summary of the meeting (PDF), and Mike the Mad Biologist came out in qualified support of further regulation. The PHG Foundation endorsed the GNZ consensus statement, and reiterated the regulatory framewhat that they have suggested in the past. Mary Carmichael cautioned against genetic exceptionalism, John Hawks outed himself as a genetic libertarian and Razib Khan discussed just how much society’s approach to medicine needs to change before we are ready for the genetic data deluge. John Derbyshire condemed the FDA on the National Review website, Matthew Herper defended them on the Forbes website, and Dan clarified exactly what was and wasn’t said at the meeting over at Genomics Law Report. There is a lot more coverage out there (as a quick scan of Google News reveals). What is clear is that this issue has captured people’s imaginations, and the FDA must be feeling the pressure to show that it is listening to the public response. [LJ]

The New York Times health blog, “Well”, reported on a recent genome-wide association study of maximum oxygen uptake during exercise (considered a gold standard of cardiorespiratory fitness) published in the Journal of Applied Physiology. This is a really interesting phenotype from the perspective of personal genomics, but unfortunately the study was under-powered and over-interpreted. The initial GWAS of 483 samples produced a handful of potentially interesting regions of association, but none were consistently replicated in small follow-up collections (in fact only a couple were even nominally replicated in any of the additional samples). Much of the discussion of the paper focused on modeling the phenotype using the SNPs from the GWAS, even though they haven’t been demonstrated to be associated beyond a reasonable doubt. [JCB]

Genetic RIsk Prediction Studies (GRIPS) that assess the ability of genetic data to predict disease in clinical settings often suffer from a lack of consistency, and often leave out key details. To try and bring order to the chaos, a group of epidemiologists, geneticists, statisicians and others recently had a two-day meeting to hammer out a consistent set of guidelines. The result is the GRIPS statement, a 25-point guide to what should be included in such studies, published in both PLoS Medicine and the European Journal of Human Genetics. However, while the report standardises what these studies should report on and include, it does not make any judgements about what models or measures are best. This is a shame: I for one would like to see a requirement that people stop using “risk allele counts” in disease prediction studies, which are akin to deciding who won a football game based on which team kicked the ball more times. [LJ]

Once again, our own Carl Anderson has a paper in Nature Genetics, this time on a GWAS of Primary billary cirrhosis, and once again, he refuses to write about it, leaving me no choice but to quote from the press release:

“To gain an insight into the causes of primary biliary cirrhosis we compared genetic data from patients and healthy volunteers and found 22 regions of the genome that differed significantly, 15 of which had not previously been identified,” says Dr Carl Anderson, from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and one of the senior authors on the paper. “By scrutinising the genes within these regions we were able to identify biological pathways that appear to underpin the disease, thus prioritising these for future research and highlighting their potential for therapeutic intervention.”

The paper (on which Kate is also a primary author) describes the discovery of 12 entirely new genetic regions associated with the disease, along with three additional loci discovered through a meta-analysis with published data. It supports the role of three impotant biological pathways in the development of the disease. If you want more information, you can read an interview with Carl in GenomeWeb. [LJ]

RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter

Kate is not only an author, but one of the joint first authors!

[Fixed! – ed]